Welcome back to Moldova Matters! This article is written by Journo Birds. Moldova Matters is collaborating with Journo Birds to bring their great content about culture and life in Moldova to our readers. You can follow Journo Birds directly on Medium, youtube or facebook.

Moldova is trying to escape Moscow's control and move closer to the European Union. But the clock is ticking, and this year will show if it's possible.

Only five years ago, activists clamored for democracy in Chisinau's central park. The local oligarchs were dragging Moldova towards dictatorship.

The flags and megaphones are gone for now. A few of the most corrupt politicians have fled. Moldova freed itself completely from the Russian gas. And in late 2023, the EU Council decided to start accession negotiations with Moldova.

In reality, nobody knows where this year will take Moldova. Moscow's efforts to maintain control in Moldova are still very evident.

The Russia-controlled territory of Transnistria is holding the country back. The Russian propaganda and cyber attacks are still ongoing, and Russia-friendly politicians are growing in popularity. Will Moldova even have a chance?

Many locals on the street are hopeful. For those we spoke to, the EU grants safety, something that Moldovans, living close to the war in Ukraine, desperately need. But only some think the EU is the only path forward for Moldova. Tatiana Calian (41), hurrying through the park, expresses reservations: "I find life in the EU comfortable, but we should remain independent - not aligned with Russia, nor with Europe."

It's a cold winter day, and she has tightly wrapped the scarf around her neck. “I don’t think we need to depend on someone else." Similarly, Vadim Antimir (29) doubts Moldova will join the EU anytime soon, citing problems within the EU.

Soon, they may be asked to cast their vote. Moldova's pro-European president, Maia Sandu, has declared that she will rerun for the presidency in the upcoming elections in late 2024. She has also asked the Parliament to prepare for the EU referendum then.

If it was to happen, nobody could predict the outcome yet. There is no clear consensus at the moment. The latest poll by Public Opinion Barometer from August 2023 shows that 49.7 percent of the people would vote to join the EU. 32.8 percent would vote against it. But the fact that half of the population supports joining the EU is remarkable, considering Moscow's hard work to prevent that.

One key player here is Romania, with its special citizenship program.

Many Moldovans are already EU citizens

Moldova is in a unique position as many Moldovans already have strong ties to the EU - in fact, they are already EU citizens.

Moldova's neighboring country, Romania, grants citizenship to those Moldovans whose parents or grandparents lived in this land before 1940 when Moldova was part of Romania. The paperwork can take years to finish, but owning an EU passport outweighs the hassle.

According to the Ministry of Justice in Romania, over 640,000 Romanian passports were granted to Moldovans by 2020. Including Moldovans in their homeland and over a million living abroad, at least every sixth Moldovan owns a Romanian passport. The latest and more precise data is difficult to obtain.

With this unique position, Moldova could become the first EU country that had a mass exodus before even joining the union, the EU Ambassador in Moldova, Janis Mazeiks, told us during the interview at the EU's headquarters in central Chisinau. "I can't think of any country where large-scale relocation would have occurred before the EU accession," Mazeiks added.

In every Moldovan family, someone lives and works abroad. They hear the stories, they see the photos on social media. They have the possibility to see that life could be better for those in the EU. Besides, the Moldovan government will open polling centers abroad so that the diaspora could also vote. Most of them live in the EU, typically in neighboring Romania or Italy where the language is similar and easy to learn for Moldovans.

As a Latvian national, Mazeiks parallels the Baltic states, where people did not have similar freedom of movement before joining the EU in 2004. When Moldova applied for EU membership, its GDP per capita was at 33% of the EU average and those who wished could leave.

This has brought up another issue. In Mazeiks' view, the main problem Moldova is facing now: retaining talent. How do you inspire people to stay and make changes they want to see? How do you build a country without its talents?

He remains hopeful. If the current government will stay on the pro-reform and pro-European agenda, Moldova can join the EU by 2030 at the earliest, Mazeiks believes. At the same time, the country's pro-Western president, Maia Sandu, shared hopes of joining even before that.

The shift towards the West is recent but significant. Moldova ceased Russian gas imports two winters ago despite past dependence and manipulation. "In two years, the country has shifted from 100% dependence on Russia to essentially 100% independence from Russia," Mazeiks added.

A big year ahead

Cutting the cord of the Russian gas was not easy for Moldova. Manipulating with energy has been Russia's main tactic to control Moldova. "Every year, every winter, for many years, we were uncertain about receiving gas because the contract, somehow, always expired on December 31," explains Iulian Groza, Executive Director of the Institute for European Policies and Reforms in Moldova. The Moldovan government was afraid to anger Russia, fearing losing the main heat source in the cities.

After giving up Russian gas, inflation rose to 35% but is now at 4.2 percent as of December 2023, according to the National Bank of Moldova.

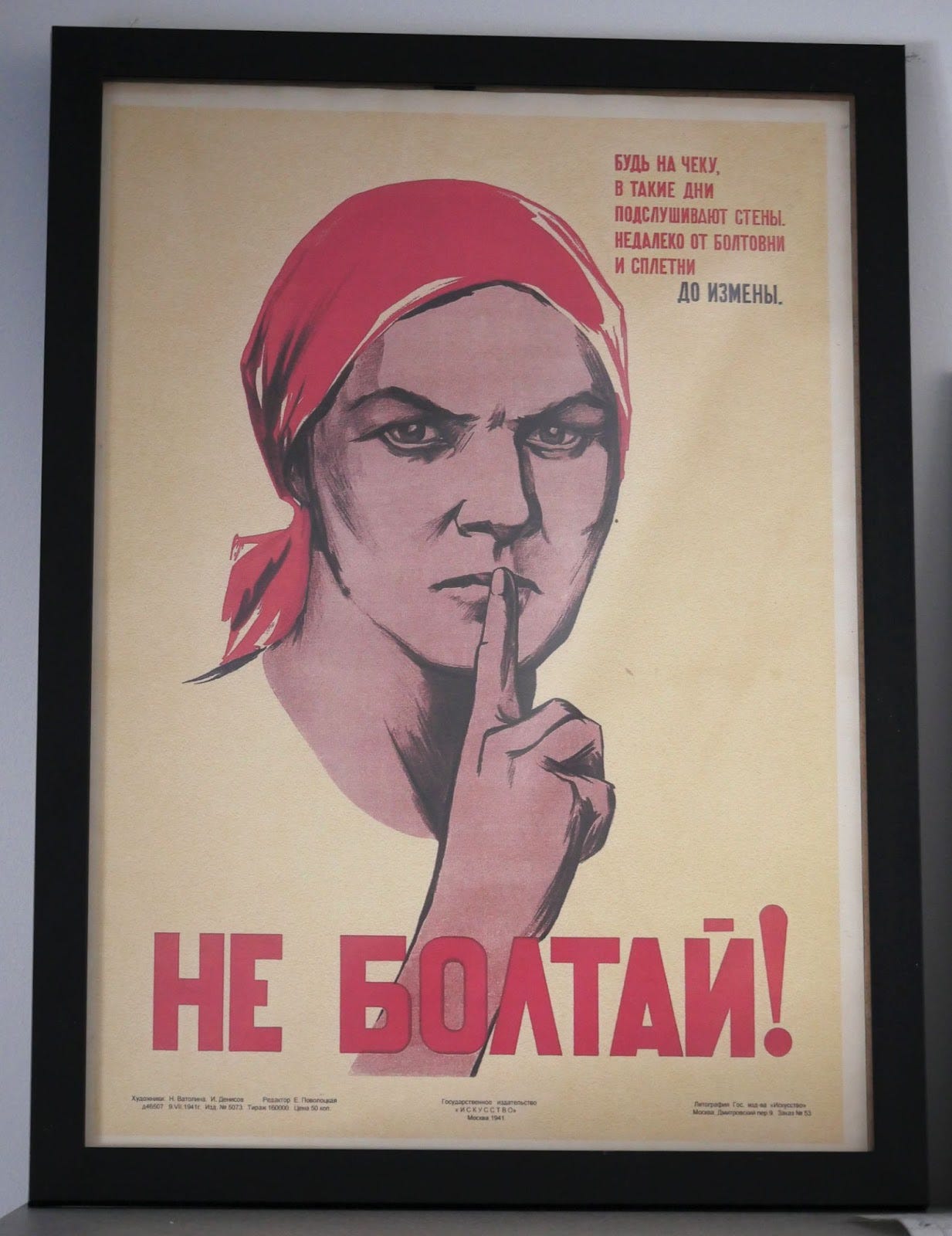

Apart from energy, there is a strip of land, a stateless territory, Transnistria, that Russia has been using since the 1990s to keep Moldova under its control. Transnistria is a self-proclaimed, pro-Russian stateless territory. There are still some 1500 Russian soldiers “guarding” the territory. Zona de Securitate is Moldova's first independent media platform that covers Transnistria-related topics. Their founder Irina Tabaranu regularly - and secretly - visits Transnistrian territory and speaks to the people there to understand what is going on. She could be jailed when caught. She says that people in Transnistria don’t speak their minds. It's a place without freedom of speech, opinion, or press. Tabaranu keeps her office in Chisinau for safety. We met her there.

She told us that she is afraid of the EU referendum. “I think they want to organize the referendum too soon. I am afraid the people will say “no” [to the EU],” Tabaranu says.

Irina Tabaranu is one of the very few journalists courageous enough to secretly sneak into the territory of Transnistria regularly to speak to the people there.

Too much, too soon?

The referendum wouldn't be organized in Transnistria since “it is not controlled by the constitutional bodies”, as President Sandu explained to the local media, but people can claim their vote in the nearby voting stations by crossing the so-called border.

Tabaranu explained that the Transnistrian residents don't see the EU as their enemy, but rather NATO and the Moldovan government. “They have economic connections with the EU, exporting goods there,” says Tabaranu.

With or without Transnistria?

Tabaranu can’t see how Moldova could join the EU without the Transnistrian territory. With the so-called Russian peacekeeping mission and Russian checkpoints near Chisinau - would the EU even accept such a scenario?

At the same time, why should the rest of the nation be punished and rejected from the EU because of Transnistria? Moldova cannot be held hostage to this situation, believes Janis Mazeiks.

Russia remains persistent in holding Moldova in its grip, closely scanning the political landscape and the sentiments, playing the long game. Russia, presumably, is already preparing for the upcoming elections. There have been many cyber attacks attempting to paralyze the Moldovan government and infrastructure. One of the most prominent fugitive pro-Russian magnates, Ilan Shor, recently left his hiding place in Israel to meet a Duma member in Moscow.

In this hybrid war, Moldova faces the challenge of implementing EU legislation and standards, combating corruption, and preparing for an evaluation, which is expected in March this year. Negotiations should start in spring.

The EU negotiations will bring investment and infrastructure to Moldova. Still, the country’s readiness for the Western path will be tested this year as it prepares for a referendum that could define its relationship with Europe for future generations. Things could go either way.

TIMELINE

A Path from Russian Influence to EU Integration

27th August 1991: Moldova declared its independence from Soviet occupation.

1990-1992: Clashes between the so-called Transnistrian breakaway region forces, supported by Russia, and Moldovan police.

1992: The United Nations formally recognized Moldova as an independent state.

1993: The government introduced the national currency, the Moldovan leu.

1994: Moldova joined NATO’s Partnership for Peace program and granted autonomy to Gagauzia.

1995: Moldova became a member of the Council of Europe

Early 2000s: An economic crisis led to an exodus of Moldovans seeking employment abroad.

April 2001: Moldova became the first post-Soviet state to see a non-reformed Communist Party return to power.

2006: Russia imposed an import ban on Moldovan and Georgian wines

2009: Despite winning the elections, the Communist Party’s victory led to widespread protests. Four Moldovan parties formed the Alliance For European Integration, sidelining the Party of Communists.

September 2009: Communist Vladimir Voronin resigned after leading Moldova since 2001. Within the next years, oligarch Vladimir Plahotniuc secured his power, becoming also the leader of the Democratic Party of Moldova and a member of the parliament.

2012: After three years and three acting presidents, Nicolae Timofti was elected president, marking the first full-term president since Voronin.

June 2014: Moldova signed the Association Agreement with the European Union.

2014: A banking crisis unfolded as Moldova’s central bank took control over Banca de Economii and two other banks amid a fraud scandal involving Moldovan-Israeli oligarch and politician Ilan Shor.

2016: Socialist, pro-Russian Igor Dodon was elected president.

June 2019: The NOW Platform DA and PAS formed a government with the Socialist party, appointing Maia Sandu as prime minister.

2019, Ilan Shor and Vladimir Plahotniuc left the country.

November 2020: Pro-European opposition candidate Maia Sandu defeated Igor Dodon to become the first female president of Moldova.

July 2021: The pro-European Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) won the parliamentary elections.

February 2022: Amid Russia's war in Ukraine, Moldova accelerated its EU membership efforts.

3rd March 2022: Moldova submitted its EU membership application.

23rd June 2022: Moldova was granted EU candidate status.

28th June 2022: The EU announced a €1.6 billion support and investment program for Moldova.

2023: The Prime Minister confirmed Moldova's independence from Russian gas, highlighting integration into the European energy network.

December 2023: Formal EU accession talks began.

2024: A referendum on joining the EU is planned for autumn.

2030: Moldova targets EU accession.

Great article David. So fascinating how such a small strip of land with no international recognition seemingly controls so much future destiny.

Trying to buy a coffee but it’s not working