Welcome back to Moldova Matters! This article is written by Journo Birds. Moldova Matters is collaborating with this team of journalists to share their stories about Moldovan culture and life. You can follow Journo Birds directly on Instagram, Facebook, YouTube or their website.

The reason why Chisinau's block-of-flat architecture was particularly unusual during the Soviet Union era.

What city symbol makes you dig through libraries to find its exact construction date? The famous City Gates of Chișinău never sought this status, but their prominence granted it. Ordinary people take care of this symbol of Chișinău, which is simply their home.

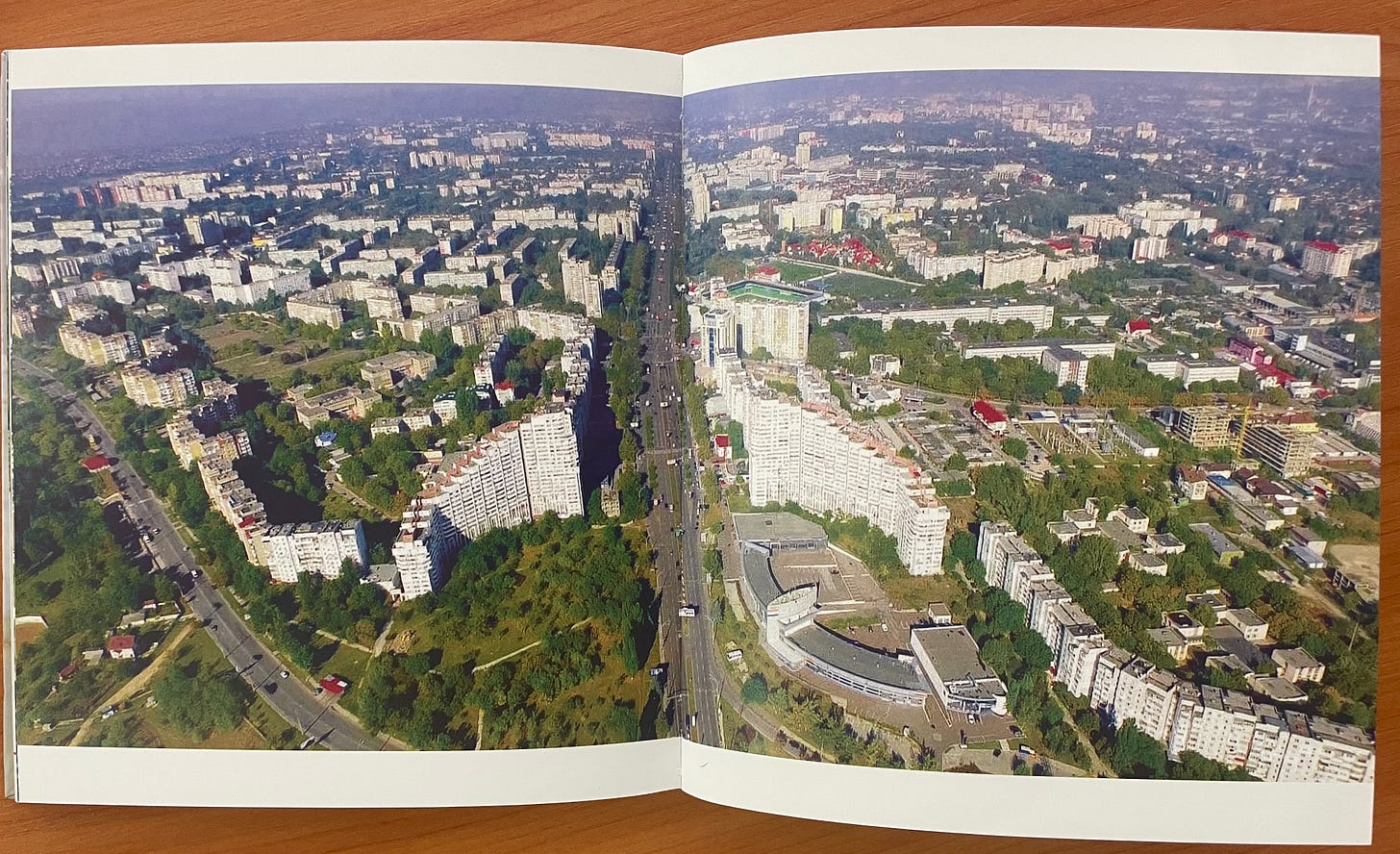

86-year-old Raisa Banteleievna has been living in Moldovan capital city’s symbol from the very beginning. Chișinău’s "Gates of the City" is an apartment building featured in pictures and postcards of the capital. For those entering Chișinău from the south, the apartment building is designed to resemble an open gate in the Moldovan folk style. Moldovans are welcoming, so an open gate is a fitting symbol for this country.

Coming from a Ukrainian family in the Transnistria region, Raisa lives with her son in a three-room apartment in the left tower (when approaching the city). This elderly lady takes care of the garden of her tower building. Walking in the park behind Raisa’s home, you can see that while the once impressive building may be slowly falling apart, the garden with roses and cherry trees is well-maintained.

The residents take pride in this garden. They come to pick cherries here, and for a moment, the day feels a little bit more special. They say it’s thanks to Raisa.

We find Raisa selling flowers and berries in front of a nearby restaurant.

She also tends to another garden, where she grows flowers and vegetables to sell at the local street market. We buy all the flowers from her for a couple of euros, and Raisa shares her life story with us on that sidewalk.

After working in a sewing factory for 55 years, she retired a couple of years after moving into a brand-new apartment with her son, who has a disability due to a childhood trauma. Raisa's memory might fail her with numbers, but she recalls the feeling of moving into the brand-new City Gates building. “The tower seemed like the biggest and most beautiful building in Chișinău!” she remembers. They celebrated with others from the sewing factory when it was finally ready for moving in.

The struggle to gather information about this monumental building in the capital city of Moldova is real. You can find Chișinău's City Gates on postcards, but to pinpoint the exact year they were built, you have to dig through libraries. Even after discussing with local historians and architects, the closest we could get to an exact date for their finishing was the decade - in the 1980s.

Some writings mention the year 1986, but photographs from that period show that they were not fully completed. Another source suggests that the first residents moved in in 1987.

Everything for a happy life

Most likely, this is because they were never actually finished, as often happened with large Soviet projects. Initially, the Gate project was even more ambitious.

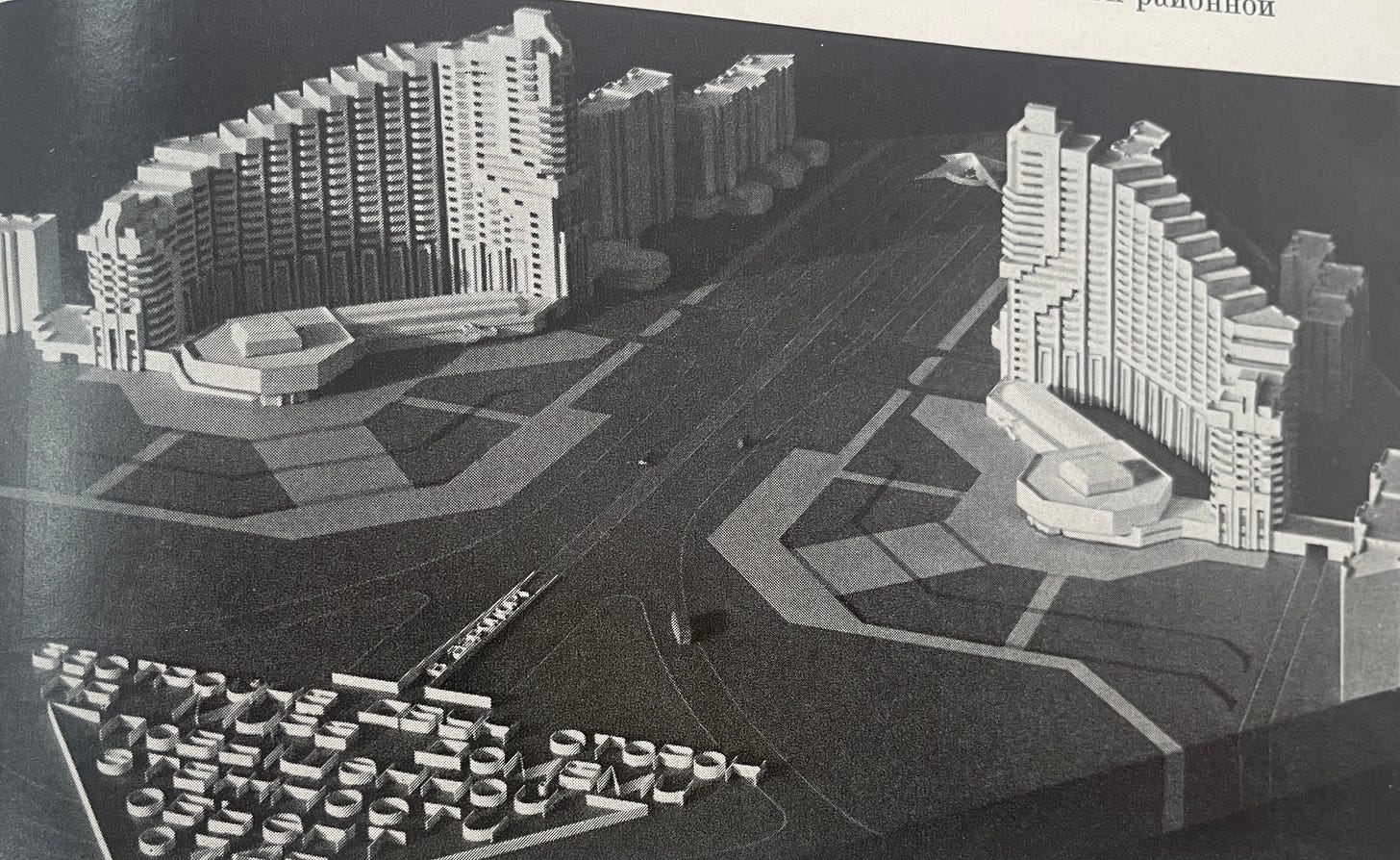

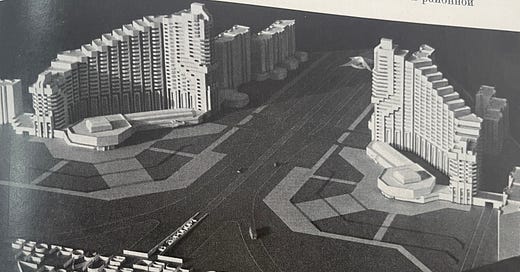

A Soviet book on Moldova's architecture sheds light on the grand plans for Chișinău’s Gates. The project was supposed to be completed after 2000, encompassing the entire district.

The Soviets proudly declared that urban planning must look into the future and envision what the environment surrounding a person will be like in the 21st century. The Gate project exemplifies this vision, described as “everything needed for city living.” However, reality was often much different, as was frequently the case when comparing Soviet proclamations to actual outcomes.

Moldovan curator and urban researcher Stefan Rusu writes about the sporadic mentions of Chișinău in Soviet literature, which were especially critical of the inconsistencies in city planning and development while only occasionally highlighting notable public or residential architectural projects. In the Soviet Union, peripheral Chișinău was often compared unfavourably to other USSR capitals like Tallinn, Riga or Vilnius.

Rusu suggests that Chișinău's location at the western edge of the Soviet Empire made it an ideal place for experiments. The historical city was bombed during World War II, leading to its modernization based on socialist standards. The Gates of the City are one example of those experiments. The plus side of that extensive testing is that Chișinău is much more than just Khrushchyovkas and Stalinkas (typical Soviet-era apartment buildings).

The city of experiments

“Chișinău was a step ahead of other Soviet republic capitals in its testing of a range of standardized residential buildings,” Rusu writes in the Architectural Guide of Chișinău, one of the best overviews in English.

Chișinău's Soviet-era architecture certainly stands out compared to the capitals of other post-Soviet countries—the State Circus, interesting residential building complexes shaped like sailing ships or toothed wheels, and more.

The City Gates were designed by Yulia Skvortsova of the Chișinăuproiect Institute. However, it is said that the idea came from Yuri Tumanyan, who was the chief architect of the city at that time. He also was part of the team that designed the presidential building in the city center.

Both gate towers rise to 24 floors. Rusu writes that the floors are made of large prefabricated panels that are the size of a room.

The Soviet Union collapsed, leaving the gate project unfinished. But Moldova was free. With the Perestroika shift to more autonomy in the former USSR, it was uncertain whether the project would have been completed even if circumstances had been different.

Locals criticise that the gates now only serve as a reminder of how they once looked. Up close, they feel embarrassed that their city symbol is in poor shape. Raisa Banteleievna worries about that, too. She does what she can and makes at least one corner of the building more beautiful.

Her life has not been easy. She was left alone raising two kids, had to work a lot, and an accident with the elevator left her son with a disability in childhood. Now, living on the 14th floor, the elevator is essential for her family’s daily life.

The once high-tech speed elevators are still in pretty good shape, but standing on the precarious balcony of the 20th floor seems scarier. In the coming years, hundreds of thousands of people living in former USSR residential buildings will need to pay attention to the safety of their homes in all the post-Soviet states. Soon gardening alone won't be enough upkeep for these buildings.

This was fascinating! I have a deep curiosity for Soviet architecture so I really enjoyed this. Thanks for sharing!