Explainer: Cake in Chisinau, but no Bread for Export

How the war and Moldovan government policy are putting local farmers in an impossible position

By Kelsey Walters, guest writer for Moldova Matters. Follow Kelsey on Facebook or Twitter for more!

A Global Food Crisis is Brewing

This month the Economist released an article called “The Coming Food Catastrophe” outlining how Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine is threatening food security and laying the groundwork for famine in far flung parts of the world. The story led the magazine with cover art showing wheat stalks made of human skulls driving home the point that the crisis is projected to be severe enough to cause widespread starvation, death, and political unrest.

The primary driving cause of this crisis is Ukrainian grain being “stuck.” With Russia’s blockade of Black Sea ports and the general breakdown of supply chains and logistics in Ukraine last year’s harvest cannot be brought to market and the new harvest will have no storage facilities to be put into. Combined, Russia and Ukraine represent around 16% of the global cereals market and India’s recently announced export bans on wheat are helping drive a surge in prices globally. The most dire predictions focus on various countries in Africa which rely heavily on Ukraine for wheat and which do not have the purchasing power to chase ever rising prices on the global market.

Meanwhile, in Moldova citizens are grappling with projected 31% inflation over the course of 2022 primarily driven by food and energy prices. This has led the Moldovan government to take action in order to prevent the price of staple goods from rising higher. Export bans are in place for Moldovan wheat and cereals and price controls limit the markup on various other products in the market. In theory, this benefits consumers and attempts to head off the political instability that can plague a country when the price of bread and staples skyrockets. But Moldova’s economy relies on agribusiness with around 16% of the country’s GDP and 45% of exports driven by agriculture and food processing. In this article we will dive into the challenges facing the agriculture sector and the unintended consequences of the government’s policies in this crisis.

Photo: Kelsey Walter’s family farm in Causeni being visited by former US Ambassador James Pettit. The farm specializes in producing cereal and oilseed crops.

Timing is Everything is Agriculture

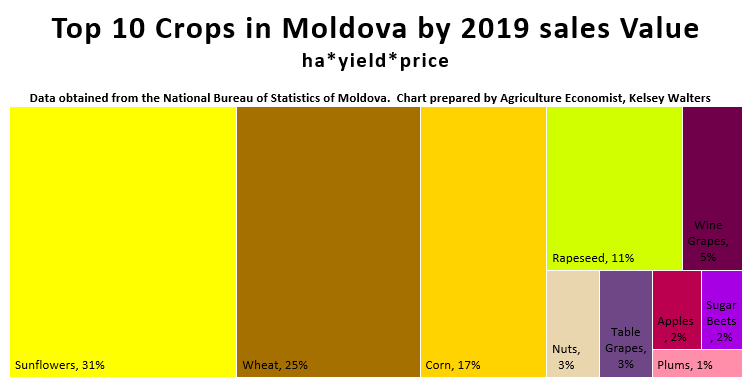

While there is a lot of talk about wheat in Ukraine, there is little mention that cereals and oilseeds are also Moldova’s biggest industry. Any time Moldovan agriculture is mentioned in the local media, it almost always focuses on the horticulture sector which includes grapes, apples, cherries, plums and more recently honey. While Moldova has a deep history as a wine making country with delicious fruits, these only make up a relatively small percentage of agriculture sales. While cute slogans about taste and high value capture media attention, the cereals and oilseed sector remains the foundation of Moldovan agriculture.

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Moldova has been highlighted in the media for its big heart and generosity supporting Ukrainian refugees, however in the discussion on global food security, Moldova has made a decision that not only hurts its own foundation, but also diminishes its contribution to the crisis.

A farmer’s strongest instinct is to plant and to harvest despite all odds. Despite their strong will and unquestionable grit, there are many variables that can influence their harvest results. Let's dig into the equation for a good crop and then discuss government policy.

The most important factor for farmers is timing. Whether farmers can get their seeds in the ground and treat plant disease in time, will make the difference between a harvest of 2 or 3 or 4 tons per hectare (if all other variables are constant).

It is critical that the bullets below are ready to go before a farmer can plant spring crops.

Access to fields - Typically spring rains can make it hard to access fields for soil prep and planting. Getting access to tank ravaged and mined fields in Ukraine is a major obstacle for Ukrainian farmers.

Labor readiness and focus - easter holidays always disrupt the ability for overtime, now the anxiety of war has played a big role in keeping farm teams focused

Spare Parts for equipment - most farmers keep an array of spare parts on hand, but it is hard to anticipate which part may malfunction. If a $50 part on a $100,000 piece of equipment breaks, then a farmer must choose to wait for the part, operate the equipment unsafely and inefficiently, or use older equipment. Sometimes the farmer does not have 3 options to choose from and the only option is to wait for parts before continuing farming.

Availability and cost of Diesel, fuel and lubricants. Not only have fuel prices increased, but farmers can’t purchase the quantity of diesel they need for harvesting.

Seeds - Quality seeds from high yielding varieties are usually ordered in advance, getting seeds delivered last minute is risky, taking whatever seeds are leftover usually means suboptimal results.

Seed treatments for soil diseases - depending on the conditions in which the seeds are planted, seeds can become moldy before germinating, treating seeds helps ensure a high percentage of seeds germinate and grow into plants

Pesticides - while pesticides are stigmatized in the general media, there is nothing worse than losing your crop to a rapidly spreading fungus or disease that could have been prevented with a low dose of mildew spray.

Fertilizer - Fertilizer comes in many forms, nitrogen liquid and granular, N-P-K mix, micro-nutrient foliar sprays, Just as a prenatal pills are suggested and iodine is essential for development, plants need certain nutrients during specific stages of development that can influence the number and weight of the developing grains.

Communications and technological signals - cellular coverage, GPS signals, a direct tie to elected authorities and a working relationship with the ministry of agriculture. This has been arguably the variable that farmers have had the most difficult time resolving this year.

When the supply chains for any of these inputs are disrupted, farmers need more time trying to get everything ready and planting is often delayed. When one or two variables are unstable, farmers are able to manage, however when all of the variables are volatile, it becomes extremely challenging for farmers to plant their seeds within the critical timing window when both soil moisture and temperature are optimum for plant growth.

Yes, higher prices throw farmers' production budgets off and because of higher fertilizer prices, many farmers have used less fertilizer on the 2022 crops, and this will also impact the harvest yield.

That said, even when prices go up, farmers continue to plant and operate their fields knowing that the margin for error is small and delays to planting become very costly. They hope that the sales price for their grain will be enough to cover the higher costs they paid to grow the crop. Prices in 2022 are fluctuating much more rapidly than in normal years which makes the calculation of the yield and price needed for a crop to breakeven …a running target. Even after calculating a loss, farmers will often still farm most of their fields because stopping their operation would be much more costly. Typically the farm leaders in small Moldovan villages are the biggest employer. Most farming businesses in Moldova are family-owned and also hire several members of the community. Farm enterprises pay employment insurances and offer additional lucrative benefits to families in the village who would otherwise need to migrate for an equivalent income. Even when a family farming business knows that it won’t make a profit, they continue to invest in their community and their lands by taking a loan or pulling from their savings to survive until the next year when the situation might be more favorable. Farming businesses in Moldova bear the responsibility to keep the rural towns alive and engaged in industry.

As community leaders in Moldovan villages, the farming businesses are the first to be asked for donations and the first to offer equipment and labor toward community improvement projects.

Impact of the War in Ukraine

The war in Ukraine has massively disrupted Moldovan supply chains and caused a spike in prices for primary inputs. But getting access to inputs on time has been just as hard if not harder than higher prices for farmers looking to produce a good harvest. Let me explain.

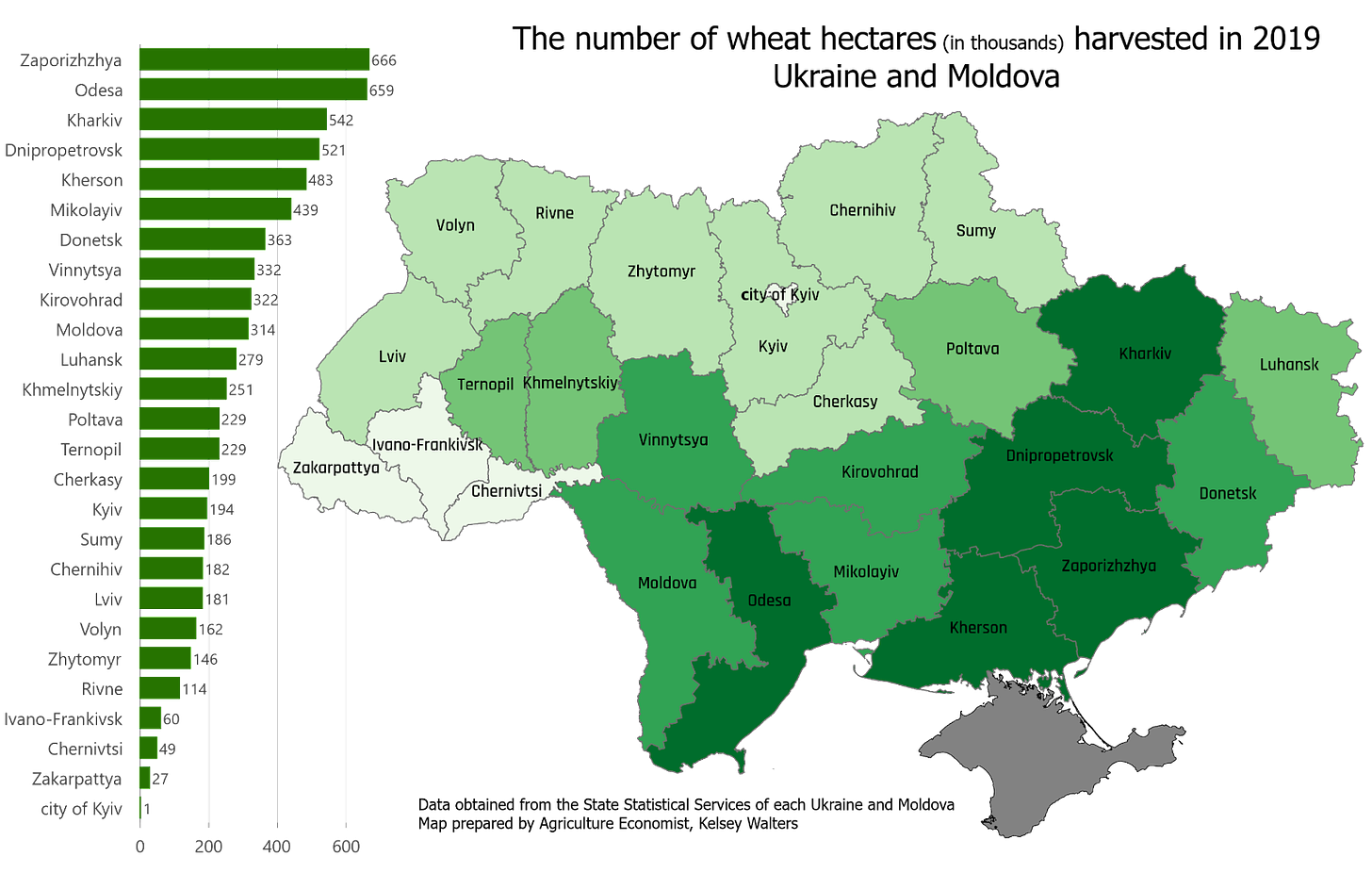

Traditionally, most agriculture inputs would be warehoused in Ukraine. Moldova’s agricultural footprint is more aligned with Ukraine than Romania which is why Moldova’s supply chain traditionally depends on Ukraine. Even before the Russians invaded Ukraine, International agriculture supply companies were starting to evaluate potential losses from an invasion and began to retain or divert stocks to Romania and Poland that were originally planned for delivery in Ukraine.

Moldova’s farmers are accustomed to receive EU imported seeds, plant treatments and spare parts from Ukrainian warehouses, and fertilizer on rail through Ukraine from Russia. Spare parts for advanced agriculture equipment and modern planters can be brought in from Romania if the logistics make sense, but the bulk of spare parts come from Ukraine.

Since the invasion started on February 24th, Moldova has looked to Romania to purchase planting materials, but sourcing from Romania has its complications. As a NATO member, Romania has security guarantees and a different risk profile than Moldova which has made Romanian trucks and drivers reluctant to cross the Moldovan border and leave NATO territory to deliver seeds and agriculture supplies. While the official storyline says that Moldova is not directly threatened, commercial businesses and private individuals read the tea leaves differently and their actions reflect a more pragmatic risk assessment. After February 24th, Romanian warehouses largely stopped delivering to Moldova. Without delivery services, Farm Supply companies in Moldova and large farmers have scrambled to find trucks and drivers to bring in farming supplies from Romania. Some of the supply coming from Romania through Moldova is then trucked to Ukraine in areas along Moldova’s borders. It takes days if not weeks to identify a warehouse and coordinate a new logistics plan and several days waiting in customs for these crucial deliveries to take place.

Government Policy is Increasing the Strains on Farmers

In 2020, Moldova experienced a horrific drought with the warmest conditions in over 40 years. In combination with the state of emergency from the COVID pandemic, the Moldovan government panicked and banned exports of wheat. Farmers tried to advocate for reason and asked that the government establish guidelines to evaluate the volume of strategic grain reserves and flour needs for public consumption. The ban on wheat exports caused the price of wheat in Moldova to be artificially low to the benefit of the flour millers, bakeries, and grain alcohol distillers. The farmers were forced to take out operating loans from banks because they were unable to sell their stored wheat. In 2020 low cost Alcohol for hand sanitizer was exported from Moldova to the EU and other countries, this product was essentially subsidized by the Moldovan farmer.

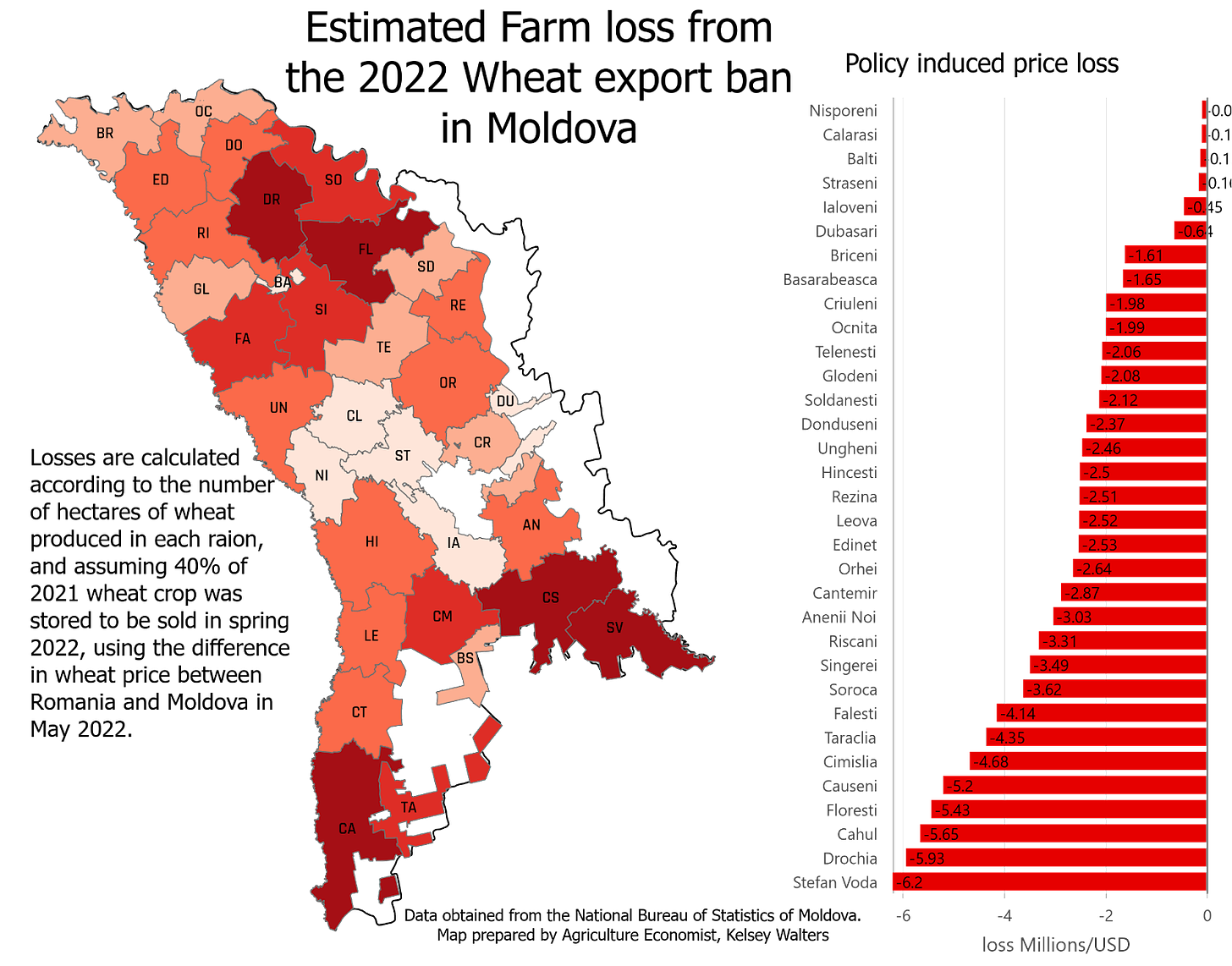

Again in 2022, a state of emergency has been declared and wheat exports have been banned. Admittedly the situation is different compared to the wheat export ban of 2020, as today Moldova is following a favorable 2021 harvest and the grain storage barns are still full with wheat after a record harvests. Because of the cool rainy year, corn set new production records in Moldova in 2021. Instead of selling wheat in the fall, farmers were trying to sell a larger volume of high humidity corn and many of them saved their 2021 wheat to be sold in the spring of 2022. Farmers need to sell the wheat they have stored to cover rising planting costs and payments on loans taken out from 2020, so the repeated ban on wheat exports is a double punishment for Moldovan farmers. Smaller farmers who have less bargaining power to buy or sell with wholesale terms are hit the worst.

Farmers are asking the same question they asked in 2020, how is the Moldovan government supporting the decision to block grain exports especially now as Ukraine is looking for ways to facilitate exports? Was this decision based on panic, or is there a calculation that justifies the economic damage to farmers? Does the government even know how much damage it is doing?

Moldova is a wheat exporter and produces so much wheat that over the past 9 years only 25% of the yearly harvest is needed to ensure that every man, woman and child in Moldova can eat half a kilo of bread each day. The ban on wheat exports feels like a government attempt to shift the burden for the price increases felt by consumers from the government to the farmers. To farmers, this feels like a soviet socialist policy reminiscent of the state owned collective farm system rather than a competitive private industry where private owners must mortgage their family homes to buy equipment and seeds. Observers should also ask what role the government owned bread company “Franzeluta” is playing in the lobby to ban grain exports rather than request bread subsidies from the government.

Again, the flour mills, bakeries, and grain alcohol distillers who are largely concentrated in Chisinau are enjoying an artificially low grain price while the price of wheat across the river in Romania is double the price in Moldova. Romanian farmers can export bulk grain shipments at double the price $0.41/kg while Moldovan farmers can barely sell a single truck of wheat receiving roughly half the price $0.23 /kg.

Excluding other factors and only considering the price impact from the government ban, Farmers are facing a price loss of over $100 million dollars estimating that 40% of the 2021 harvest is still waiting to be sold. That is an average loss of $110,000 to small and medium farms that employ on average 30 rural staff with payroll costing them roughly $70,000 per year. Even if a farmer has little choice but to cheaply sell his saved wheat just to pay salaries, the volume of wheat that he can sell is small because Moldova is saturated with more grain than it can consume. Even the largest elevators and grain buyers are only willing to buy 10% of the volume they bought before the export ban. Farmers are devastated at the prospect of selling 10% of their crop at only ½ the price.

Marie Antonette once made a disastrous statement which showed how disconnected she was with the rural farmers in France, her courtesans said “Ma’am, the people have no bread”, and she replied, “well, then let them eat cake.” While the situation in 2022 is different, it has similar characteristics of an urban bureaucracy disconnected from rural constituents. The policy to ban free trade and keep all the grain stocks in Moldova shifts the public pressure of food inflation from politicians to rural businesses, keeping the urban constituency happy with an artificially low cake price in Chisinau.

The quote should be modified to say, “M’am our neighbors have no bread” and the response from the disconnected commission in Chisinau would be “well, then bake a cake. ” International experts and watchdogs are reporting with despair as poor wheat importing countries will be consuming less wheat because of limitations from both price and volume. Lower levels of consumption in populations already plagued by malnutrition are the real (but distant) result of supply chain shocks. As Moldova has shown a big heart for caring for Ukrainians fleeing their homes next door, Moldova is performing poorly in watching out for its base. Not only is it intentionally hurting its own farmers but it is also contributing to the global food crisis by banning exports while holding a surplus.

What is the mood of farmers on the ground right now?

Put simply, farmers read about record prices for grain and global shortages but their experience is disconnected from the global market. At a time when market forces should see Moldovan farmers stepping into the gap created by Russia’s blockade of Ukrainian grain exports, instead they are left fighting their own government.

As Moldovan farmers struggle to keep their operations running in the villages, they are left out of the discussion in Chisinau. For the past several years, the focus of the donors and subsequently the focus of the ministry has been on horticulture production which has come at a cost to other agriculture sectors. Cereal and oilseed farmers feel sore when the price of wheat in Romania is 11 mdl per kg exported around the world, but the media is focused on “high value” apples selling for 5 mdl per kg. Moldovan farmers think that the government is completely disconnected from rural areas and are further sabotaging the economy by being distracted by new curtains rather than staying focused on their cracking foundation. If the Moldovan government was truly seeking to support the economy, they would calculate and reserve crops necessary for food security and then liberalize trade which would result in the most impact to GDP and revenue.

As Farmers sit with warehouses full of grain and with nowhere to store the impending harvest, the quality of this grain is deteriorating. Grain warehouses need to be emptied and disinfected before harvest. Mildew and weevils that spread from holding the previous harvest too long can contaminate the new harvest further adding insult to injury.

Moldovan farmers have a big impact on GDP but a small voice in Chisinau

Traditionally, agriculture and farming interests are poorly represented in Chisinau and with more donor focus on horticulture, cereal and oilseed farmers are brushed aside even further . The fact that Moldovan farmers have such a weak lobby has been highlighted during these export bans.

Why is the lobby so weak for the 930 small and middle size farmers who pay salaries to over 28,000 rural employees in Moldova and produce cereals and oilseeds (84% of all agriculture sales)? One explanation is that traditional sectors have a harder time getting an audience because the Moldovan government has been distracted by international donors who dominate the agenda with programs that support niche sectors. International donor funding makes it more lucrative for member based “farm associations” to shift their focus toward the topics that are most likely to land a service contract than to focus on lobbying and building resilient rural networks which strengthens farmers' role in the democracy. While International programming can be positive, it is counterproductive if it competes with local initiative. The Ministry of Agriculture has traditionally offered calming leadership for farmers, but it is no secret that they are short-staffed and poorly paid. With an overwhelming workload and uphill battle to inform parliament about the hard issues facing agriculturalists, it’s no surprise that flashy international programs have distracted the Politicians and Ministry from staying focused on their foundation.

International programming can play a helpful role, and there have been noted reforms and gains made in the agriculture sector because of donor support, specifically reform to update phytosanitary norms and certification processes to facilitate exports, along with a push to streamline the status of day laborers working seasonally on farms. Unfortunately the expenditure and impact of international donor dollars remains largely in Washington and in Chisinau. Robust media budgets ensure that “ribbon cuttings” and “visits to the field” are promoted on tv and social media, but in the last 10 years no program seems compelled to facilitate deeper reforms that would ease the paperwork burden for small farmers seeking to expand from hobby farm to LLC status. While most agriculture development programs are “showhorses,” Moldova actually needs a plow horse approach to get to the root of these issues.

The ministry of agriculture sorely needs international support (not distraction) to bolster its emergency prediction and response abilities and present a solid plan for domestic food security that does not rob farmers to subsidize processing companies in Chisinau. With a solid economic grasp of the private sector drivers of the agriculture economy, the Ministry of Agriculture would be able to push back against the conflicting state owned agricultural interests. The Government of Moldova owns a variety of influential players in the “agriculture value chain” and representatives of these are embedded in the government further challenging the voice of real farmers. In this article we have already posed the question about the influence of the government owned bread company, but there are other more state agencies that should pass a “value adding” audit or be flatly privatized or defunded.

Moldova has made leaps and bounds of progress to recover from production declines due to the collapse of the soviet collective system and nascent privatization. Specific programs have successfully supported farmers with streamlined loan mechanisms to modernize their equipment, and global supply companies have increased Moldova’s yield potential by making modern crop inputs available. Leaping into 2022, Moldova needs support to modernize its agriculture policy frameworks to enable competitiveness and private sector initiative in the agriculture sector regardless of the crop produced. To the point, Moldova needs deep agriculture policy and streamlined tax reform, it doesn't need more ribbon cuttings and demonstration plots.

It is easy to say that the Chisinau centric government, International donors, and now the Ministry of Agriculture have lost the trust and engagement of farmers in the primary agricultural sectors of Moldova. It is harder to discuss how this trust can be won back.

How Can Moldova Protect Farmers and Fight Food Inflation?

Below are some Broad outlines of policy recommendations for the Ministry of Agriculture. These could also be used as program concepts to be funded by international donors seeking to make an impact for all rural enterprises.

Calculate the minimum required food security stocks and buy and store them immediately after harvest when the price will be lowest.

Place limitations on the timing when the fiscal authorities can “audit” farms, (tax authorities should be banned from making audits during harvest and planting).

Provide access to open weather data and adoption of new drought monitoring indicators so farmers can make individual assessments in the spring regarding crop outlook.

Align with the hydrometeorological station in Iasi, Romania (which has already demonstrated transparency and willingness to collaborate) to send sms predictions of extreme weather events.

Design and install small weather stations in 50% of mayors offices in Moldova and allow this data to be available to the public. Monitoring accumulated rainfall, low/high temperature, and air humidity can help farmers predict their crop yield at the sub-national level with increased precision. This data must be digital, accessible in different formats, and recognized by the authorities as causal effects for crop reduction or surplus.

Ensure full transparency on the calculation, consumption and production of the “social bread’” program

Allow the subsidy system to provide a 2 to 1 match of membership dues paid by farmers into their producers associations.

Request that international donors be careful about choosing crop winners and instead provide support for specific policy reforms rather than support to specific fruits.

Bring in agriculture associations from the US & Europe (not DC based consulting firms) to assess and recommend capacity strengthening needs.

Create policy mechanisms that establish normative yields and other statistics which will develop the foundation for commercial crop insurance against hail and other maladies.

Streamline the process of transitioning from a Hobby farm to a commercial LLC.

Reduce the number of statistical reports in agriculture (which has the most reports of any industry in Moldova)

Modernize the agriculture accounting structure which is still based on Kolholz era reporting.

Apply streamlined taxation concepts from the IT industry in agriculture to allow farmers to focus on production not paperwork.

About the Author

Kelsey Walters is an agriculture and spatial data analyst from Oklahoma and a farmer in Moldova. Working between the USA and Moldova in both technology and agriculture fields she has a unique understanding of the challenge to unite rural and urban policies. Since serving in Moldova as a US Peace Corps volunteer, she has made it her calling to support the design of programs that dig deeper and address the real needs of the farming sector. She hopes that more technical solutions will be applied in both the public and private sector to increase the resilience of the agriculture community to the challenges of climate change. Follow Kelsey on Facebook or Twitter for more!

Thank you for this in-depth explanation of challenges faced by Moldovan farmers.